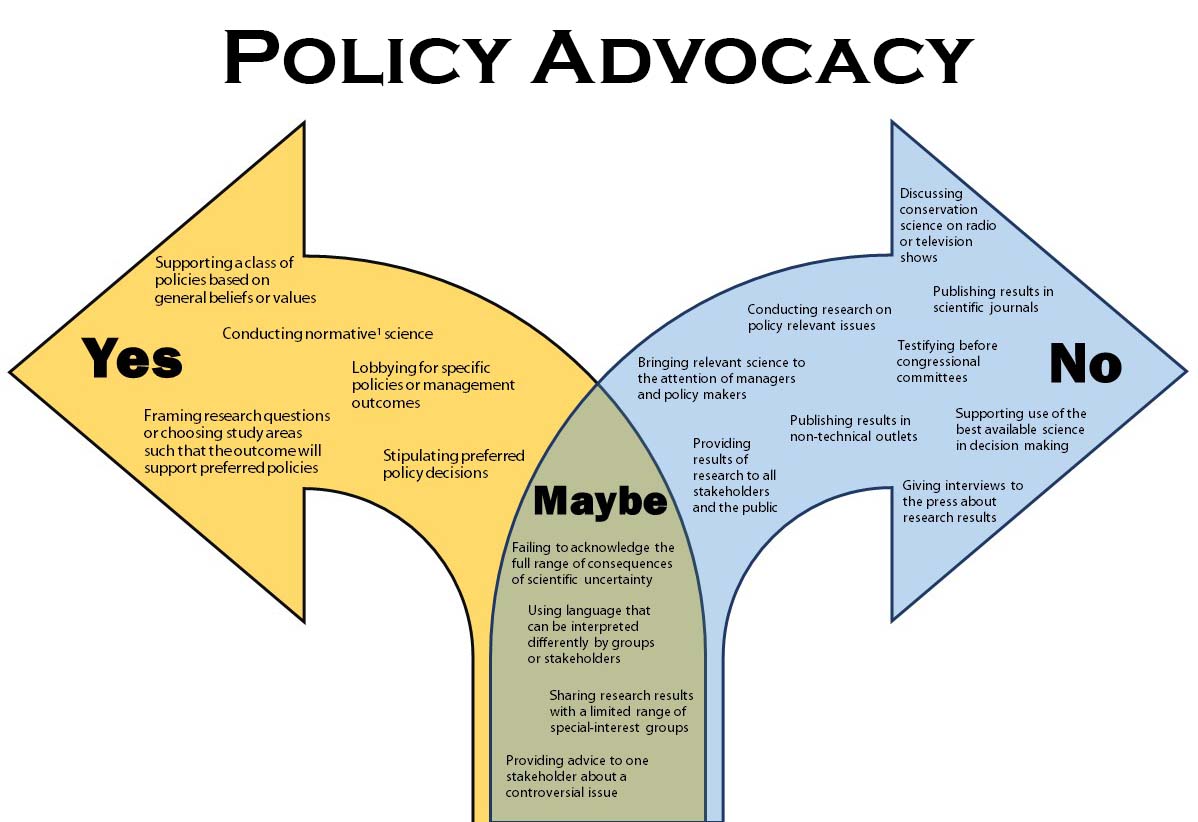

1In the applied sciences, normative science is a type of information that is developed, presented, or interpreted based on an assumed, usually unstated, preference for a particular policy.

Clipping studies are used by some groups to point out the potential ill effects of grazing on plant health. According to Trlica and Rittenhouse (1993), plant ecologists often focus on the defoliation aspect (removal of plant material) of grazing and how individual plants respond to defoliation. A large number of studies have used clipping treatments, rather than grazing animals, to defoliate plants. Ecologists often assume clipped plants and grazed plants responded equally, but many studies have shown clipping cannot be used to simulate grazing.

Finding an article that compared clipping to grazing meant going back to the 1960s. Compared to clipping, livestock 1) tend to graze plants to different heights, not to a single uniform height; 2) remove less plant material; 3) eat specific plant parts rather than the whole plant; 4) may change plant size and form by selecting certain individual plants within a species; 5) affect the build-up of plant litter differently; 6) add nutrients to the soil through urine and feces; 7) trample the area they graze; 8) change forage preferences during the grazing season; 9) affect the competition from neighboring plants through grazing; 10) do not graze all plants continuously throughout the grazing season (Jameson 1963).

In 1975, Rickard et al. reported that clipping studies do not simulate how cattle graze plants. Especially if animals are able to select among multiple plant species and plant parts over a large area. Working in south-central Washington, a 9” precipitation zone, they concluded that it would take many years of moderate grazing before shifts in plant species composition and abundance would be noticed.

Some researchers have tried to mimic grazing through clipping. They found that these clipping treatments were not as severe as the treatments where plants were clipped to a uniform height. For example, when half of a bluebunch wheatgrass plant was clipped the basal area increased by 18.6%. However, if the entire plant was clipped the basal area decreased by 7.8%. The basal area of unclipped plants increased by 5.2%. In this study, plants were clipped to a 3” stubble height just before seedheads emerged (Clark et al. 1998). When compared to unclipped plants, Stroud et al. (1985) reported that simulated grazing of western wheatgrass did not decrease above or below ground production (roots and rhizomes) provided season-long utilization (clipping) was below 80%. Tiller numbers, however, increased 28% on unclipped plants compared to plants under simulated grazing. Simulated grazing involved clipping individual plant tillers one to four times during the growing season. Clipping intensity on tillers was 33%, 67%, or 100%. For most simulated grazing treatments, season-long utilization ranged between 64 and 79%.

After an extensive review of the literature on herbivory, Maschinski and Whitham (1989) came to the following conclusions: A plant’s response to herbivory is flexible. Herbivory can be detrimental, neutral, or even beneficial for a plant depending on conditions and its ability to replace tissue eaten by herbivores. The effect of grazing on plants depends on the frequency, intensity, competition, nutrient availability, timing of grazing, and the weather.

References

Clark, PE, WC Krueger, LD Bryant, and DR Thomas. 1998. Spring defoliation effects on bluebunch wheatgrass: II. Basal area. Journal of Range Management 51:526-530.

Jameson, DA 1963. Responses of individual plants to harvesting. Botanical Review 29(4): 532-594

Maschinski, J and TG Whitham. 1989. The continuum of plant responses to herbivory: the influence of plant association, nutrient availability, and timing. American Naturalist 134:1-19.

Rickard, W.H., D.W. Uresk, and J.F. Cline. 1975. Impact of cattle grazing on three perennial grasses in south-central Washington. Journal of Range Management 28:108-112.

Stroud, DO, RH Hart, MJ Samuel, and JD Rodgers. 1985. Western wheatgrass responses to simulated grazing. Journal of Range Management 38:103-108.

Trlica, MJ and LR Rittenhouse. 1993. Grazing and plant performance. Ecological Applications 3:21-23.